We are what we think.

All that we are arises with our thoughts.

With our thoughts we make the world.— The opening of the Dhammapada, translated by Thomas Byron

I’ve been learning the modern neuroscience of perception and consciousness. It’s very different than the model I learned in grad school in the ’90s. For example, I was taught that the eyes construct an internal representation of the world on the fly. We thought hearing, sensory perception, taste, and smell worked similarly. It turns out there are integrative networks for some things like balance and eye-tracking, but vision is much more complicated. Brains are lazy by design in order to conserve energy. It’s more efficient to construct and maintain an internal mental model of the world around us. Then attention only scans for changes, which are added to update the sensory picture. Perception is essentially inside out, not outside in.

Sensory Perception

We evolved to efficiently find signals relevant for survival. Consider how the sense of smell works in everyday life. Our “default” is no-smell so signals jump out. If I have a ripe cantaloupe on the counter, I’ll smell it the moment I walk into the kitchen. Food! Once I’ve decided whether the melon will be breakfast or dessert, the smell recedes. If I smell smoke, it takes longer to fade from consciousness. Fire is dangerous and I have to be sure I know where the smoke is coming from. Once I see smoke rising from my neighbor’s chimney, the smell will fade unless it grows in intensity or changes in character.

Vision is similar. We perceive a continuous scene, our eyes actually make little jumps called saccades. Our vision is only sharp in a relatively small area. We use peripheral vision to notice light, motion, and shapes. If anything changes it catches our attention and we look at it and update the model. For example, motion and contrast as I’m walking on the local trail catches my attention. Once I’ve identified the figure as a runner and not a bear, I subconsciously add her to my internal mental picture. It seems like I’m paying continual attention to her, but all my visual system is doing is spot-checking her position so we don’t collide. As she approaches I’ll start to fill in details like her clothes and hair and check if I know her.

The Internal World

Once I learned that the internal model isn’t merely sensory, it really changed my understanding of how my mind works. The human mind actually constructs a complete internal world. My plans for the day, how current events might impact me, and what I’m having for dinner are all there. It includes my family, my friends, colleagues, and enemies. I have a useful model of my home, my brother’s home, and how to get there. I know a lot of abstract science, some useful, some not. Our mind maps are centered around the illusory self, and continually redefine and reinforce that self. The internal world can even over-ride the external one. When we’re reminiscing about past events, or daydreaming about the future, we’re in that world rather than the real one.

The mind isn’t even that good at telling the difference between inside and outside. Mentally practicing music convinces the mind that it’s practicing music, and you can get better without picking up an instrument. When you’re playing a character running in a video game, your mind increases your heart rate and prepares your body for exercise. If you think about doing a creative project, your mind might decide it’s done and you lose interest. It puts a whole new spin on the start of the Dhammapada for me. The Thomas Byrom translation in the book that sits on my shelf is: “We are what we think. All that we are arises with our thoughts. With our thoughts we make the world.”

Dukkha and Chaos

One way I think of dukkha now is distress that appears when I discover that the inside map was wrong. I’ve noticed that the bigger the mismatch is, the worse the dukkha might be. Once I started considering what inside out perception means in everyday life, I realized I constantly have expectations that my conception of the world will be correct. I expect to feel reasonably rested in the morning. I expect my coffee machine to work. I expect heat. I expect hot water. I expect my Internet to be up. I expect my car to be in the driveway where I left it. All of these things are completely stable in my inside world. Any disturbance to the way I thought my morning would go can trigger dukkha. It’s easy to recover my equanimity if I get up tired; not so easy if the car is stolen.

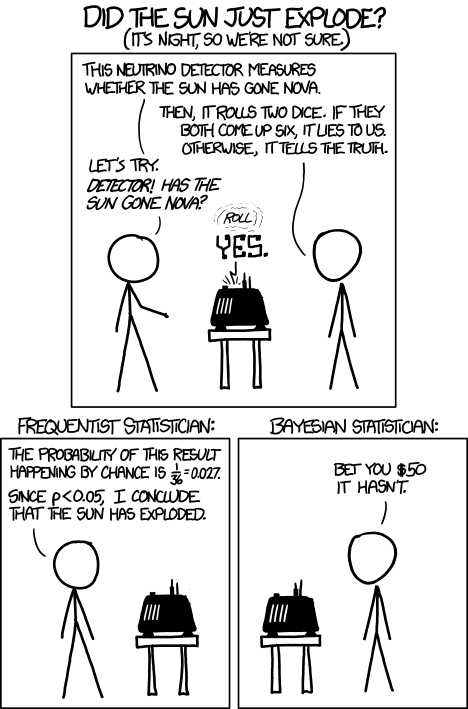

Every day, I make a Bayesian assumption that my life won’t be suddenly thrown into chaos. A lot of things could go wrong today, like a natural disaster, sudden illness, becoming a victim of crime, experiencing an accident, or suddenly losing my job. The sun could even go supernova. Our minds can’t even anticipate every catastrophe that could befall us. (Although my anxiety-ridden brain tries its best.) Instead, we’ve evolved to assume an orderly status quo based on the majority of our past experience and act accordingly.

Informing Practice

Every shift in in my internal world starts with sensory information or sometimes thought – mind is the sixth sense. Classical Buddhism speaks of dependent origination, which is the path from emptiness to dukkha. Once we are focused on something because it doesn’t match, sensory information comes into consciousness. Then we attend to it, and recognize it as an object. The process is really fast, on the order of 300-400 ms. At that point if I’m paying close attention I can notice an interesting bifurcation. Often nothing happens; however, sometimes I catch my mind in the process of deciding to create a story. That’s dependent origination.

For example, I just noticed my cuticle butter on the table, realized my nails are dry, and oiled them. There’s enough in the tin to last for a while so I move on. No big deal. However, the moment after I noticed the cuticle butter, I could equally easily have chided myself because it belongs over on the desk. Either way I’ve added the cuticle butter to my internal world, but one mental picture is fluid and the other is a bummer.

Now I’m noticing how my mind works in more detail, and what conditions create my discontent or dukkha. I’ve always had a mindfulness practice with thought awareness. However, seeing my mind catch a bit of sensory information, update the internal picture, and then immediately overly a story is different enough to be interesting. My new mental model of inside out perception is helping me understand and notice not only what I’m thinking, but the whole process of when and how my mind creates discursive thought.